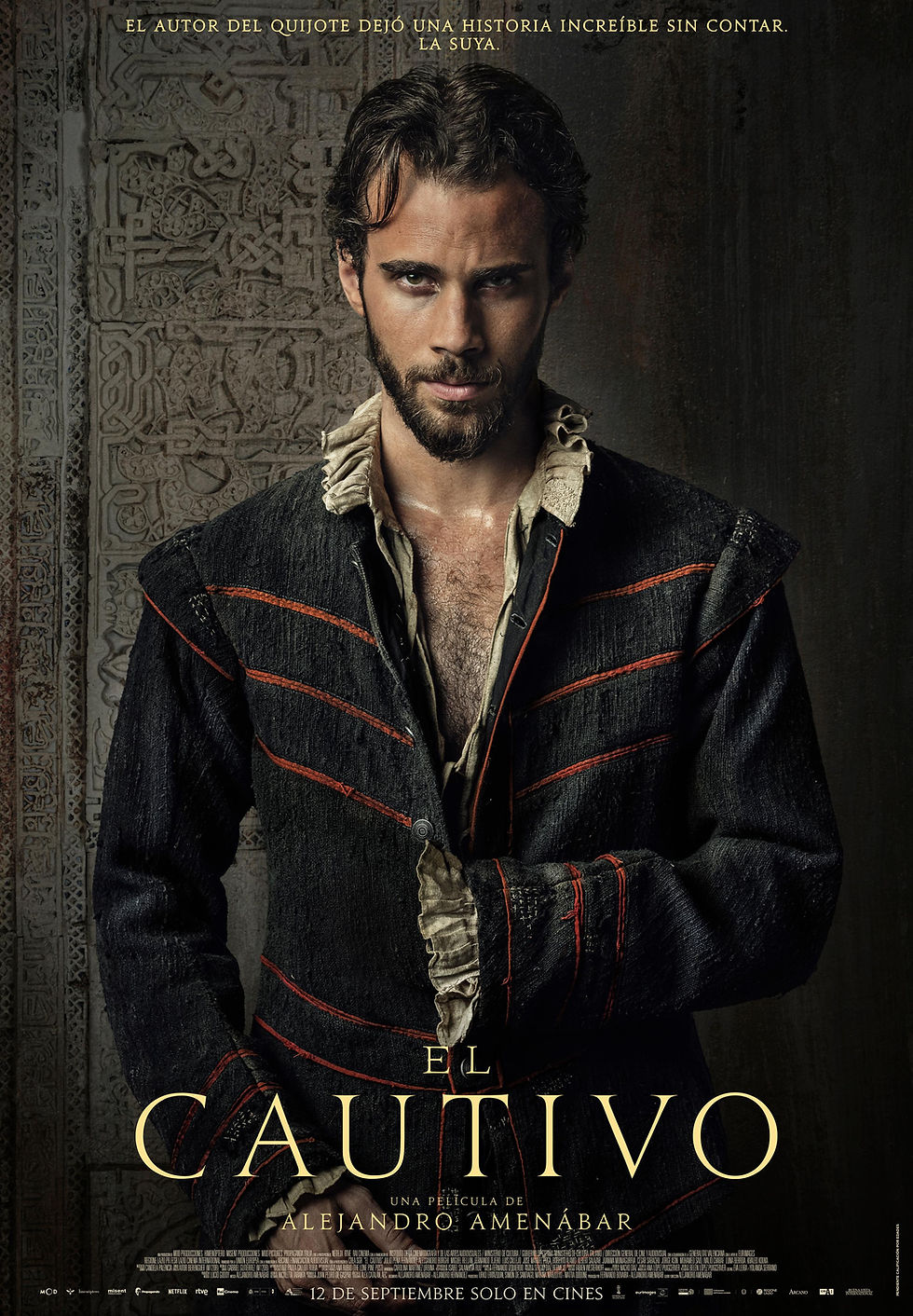

The Captive

- Young Critic

- Sep 17, 2025

- 5 min read

Alejandro Amenabar's latest is confused in its structure

“Don Quijote de la Mancha” is considered the most-read novel in the history of mankind, surpassed only in readership and circulation by religious texts like “the Bible” and “the Quran”. Yet the classic tale of a Manchegan nobleman consumed by the fantasy books he reads—who later embarks on a series of picaresque adventures with his “squire” Sancho Panza—has failed to be satisfactorily adapted to the silver screen. There have been attempts from cinematic greats like Orson Welles, Georges Méliès, and Terry Gilliam, and it held a particular fascination in Soviet Russia, where Grigori Kozintsev attempted a film version. Yet none have been able to capture the aura and mythical quality of Miguel de Cervantes’ text. Alejandro Amenábar has chosen a different take on this mythology, by adapting the story of Cervantes himself.

The Captive (2025) tells the story of when Miguel de Cervantes (Julio Peña), not-yet author of “Don Quijote,” was taken captive after the Battle of Lepanto at sea and imprisoned in Algiers from 1575 to 1580. There we see him develop his love of storytelling among fellow Spanish and Christian prisoners, and how he forms a relationship with his captor, Hassan Baja (Alessandro Borghi), the Ottoman ruler of Algiers.

Amenábar has explored historical narratives of identity before—such was the case in Agora (2009) regarding religion and knowledge, in While at War (2019) with the debate over whether one can remain neutral in a war, and even in La Fortuna(2021), his treasure-hunting miniseries about the ownership of history and culture amid ancient and modern colonialism. Thus, to take on Cervantes felt like ripe territory for the Chilean-Spaniard director.

The Captive is fascinated with exploring many themes of its historical context as well as of its main character. One is the confrontation between Christians and Muslims, which can also be found in certain subtexts of “Don Quijote’s” critique of organized religion. However, the film is equally interested in how Cervantes develops his passion and skill for storytelling, making up stories orally and borrowing from written texts to entertain both prisoners and captors. Here Amenábar nods to some of “Don Quijote’s” inspirations, such as “Lazarillo de Tormes.” Finally—and most controversially—The Captive digs into the vague historical insinuations of Cervantes’ queerness.

These are all intriguing themes to explore on film and can be woven together in a satisfactory way. Yet The Captive’sscript struggles mightily to incorporate them organically and with structure. The result is a messily assembled film that seems organized in big thematic chunks: first religion, then storytelling, finally homosexuality—so that no theme feels central or core to the story. The result is that The Captive feels hollow and decentered in what it’s trying to say. Amenábar is clearly most intrigued by the queer readings of Cervantes’ life, and while these are the most vibrant and layered scenes, they feel disconnected from the buildup in the rest of the film. Nothing is teased or hinted at; story beats and character actions seem to come out of nowhere instead.

This means that each act of The Captive feels disconnected from the rest, and without the semblance of a solid story structure, it loses viewers and their expectations of pace. At over two hours long the film isn’t boring, but its lack of direction means viewers can’t track how they should perceive the story and its beats, so that the rhythm ends up feeling long and dragging. Five minutes before the film ends, you could mistake it for being a scene in the middle of the runtime, and vice versa. This failure to follow a classic story structure means the stakes and dramatic momentum are lost on viewers completely, leaving them unmoored (pun intended).

As for the central character himself, the film’s intentions feel similar to Tolkien (2019), which tried to capture the inspirations and writing skill of J.R.R. Tolkien and his “Lord of the Rings.” While that film felt like a summary, The Captive approaches its protagonist with a sense of inevitability: of course he was always a genius storyteller; divine inspiration comes to him in various indelible images from “Don Quijote” during his imprisonment; all those around him recognize that he will be a great man one day. Gone is the context that Cervantes was not famed or recognized for his writing until he published “Don Quijote” a few years before his death at 68. This lack of deconstruction of Cervantes’ character makes him seem more like a distanced, cipher-like historical figure than a flesh-and-blood man.

Not even the explorations of Cervantes’ supposed homosexuality are used to give the character depth. We never truly see Cervantes wrestling with this identity—it simply… happens… and recedes. All of Cervantes’ decisions seem decisively assured, leaving him a genius and infallible hero, which makes him all the more unrelatable. Only a scene in which Cervantes must choose to lie to save his skin shows some semblance of internal debate and strife.

Some of this passiveness regarding Cervantes’ character may come from Peña’s performance. The Spanish actor is adept at portraying the external moments of Cervantes’ life—whether suffering, crying, or storytelling—yet missing is any interiority. Viewers are constantly seeing a Greek-mask version of Cervantes instead of a flesh-and-blood one. Peña is not helped by a script that veers in multiple directions, but he also doesn’t bring much complexity to his performance. Elsewhere it is Borghi who shines most, stealing every scene he shares with Peña, and showcasing the conflicting identities he struggles with internally. His violent acts are carried out not with relish but with a mix of sadness and resignation, which makes him infinitely more intriguing than anyone else on screen. His obsession with Cervantes is the only relationship that bleeds and crackles onscreen, whereas the central camaraderie of the prisoners feels stale and clichéd.

Amenábar, however misguided in his script, continues to be an incredibly talented director. The technical skill is evident in everything from the economic use of locations to the editing beats, cinematography, and even the musical score (always composed by Amenábar himself). To his credit, while the film wanders and feels long, none of the scenes—however incongruous their structuring—are boring.

In the end, however, a film can only go so far without a solid script and story. The Captive is a film that, while tackling a fascinating subject, fails to focus on a singular thematic core and structure, resulting in a disparate and unfocused whole. By treating its protagonist as an infallible genius, the film falters in its premise of trying to unmask and understand the “why” of Cervantes. And at the end of the day—wasn’t that the whole point of the film?

5.6/10

Comments